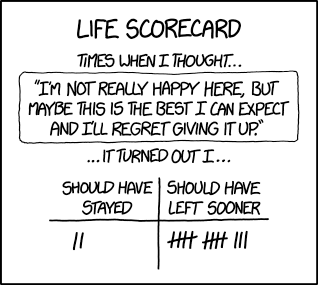

It is a truth universally acknowledged that persistence is the key to success.

Alright, maybe not universally acknowledged, but acknowledged by about 70% of internet images of motivational quotes with random backgrounds:

And acknowledged by movies, even the ones for kids:

And acknowledged by some of history’s most famous figures:

“If you are going through hell, keep going” – Winston Churchill

A fitting thing for the man to say, considering he could be quite the devil himself.

Drawing the path to success

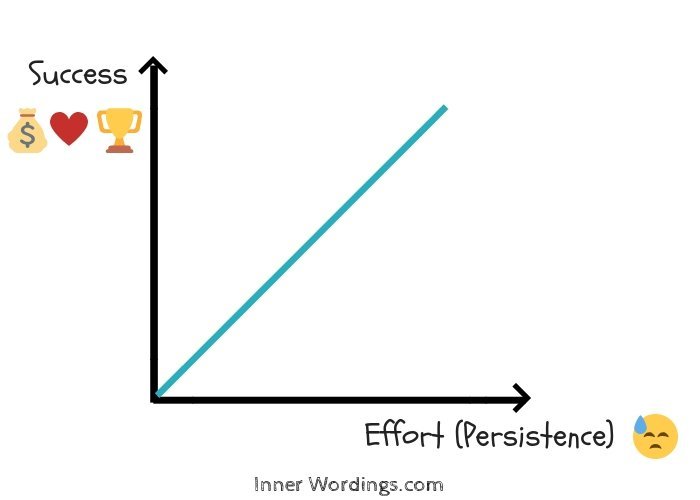

All this pervasive messaging means that from the time we’re young, we develop a very simple understanding that for any task we face (more money, relationships, status etc.) more effort = more success. Basically, this:

This is great advice. Persistence is irreplaceable when it comes to achieving most things in life. Too many people give up on something once it gets difficult, when they should have stayed with it and made it work.

But are there situations when we should not persist? Can we persist too much with persistence?

Understanding sunk costs

Let’s take an example from the world of business. In 1962, Britain and France decided to put away centuries of rivalry and make a baby: the Concorde, the first supersonic passenger airplane.

It became clear very early on that Concorde was never going to be financially successful. In fact, the British government privately regarded it as a “commercial disaster” that they “never should have started”.

This didn’t stop either the British or the French in spending billions more of tax-payers’ money on the project for the next few decades. They had already invested too much to just throw it all away. (National pride and diplomatic relations were also at stake.)

Eventually, the lack of profitability and safety concerns (after the AirFrance crash) grounded the Concorde permanently.

The story of the Concorde fallacy shows how persistence can go very wrong. Persisting in something is not generally a good idea if the major reason for persisting is that we’ve already invested a lot in it, i.e. we persist because of our sunk costs.

Sunk costs refer to any investments/effort/resources that have been made in the past and cannot be recovered or recouped at all. Because sunk costs will remain the same regardless of whatever we choose to do, we should ignore them when making future decisions.

Britain and France were never going to get back the money they had already invested in the project. So why spend even more? A completely logical robot would never make this mistake.

The sunk cost effect

Unlike robots, people and governments are not fully logical. We do not ignore our sunk costs; instead, we make our future decisions based on them. This is called the sunk cost effect or sunk cost fallacy.

The sunk cost effect means, that despite evidence that the cost of persisting on this course of action will be greater than the benefits, we continue anyway.

This is not how we make good decisions. Good decisions are about maximizing our future gains, not about justifying our past actions.

The sunk cost fallacy is why people stay in movie theaters despite realizing in the first 5 minutes that the movie was horrible. “I already paid for it, so I need to get my money’s worth.” The money’s already gone; watching the movie won’t bring it back. Would you rather spend the next 2 hours of your life watching a movie you hate, or doing something you like?

It’s why people stay in toxic relationships that they know deep in their hearts they should leave. “But what about all the years we spent together???” Again, there’s no way you can get those years back, whether you stay or not. Would you rather stay in a relationship that’s definitely not working, or move on and possibly find happiness?

It’s why students stay on particularly difficult test questions, even when they have no clue what they’re doing anymore. “Oh my god, I’ve spent all my time on this question, now I need to get it right!”. They forget the strategic thing to maximize their score would be to leave that question, and answer easier ones.

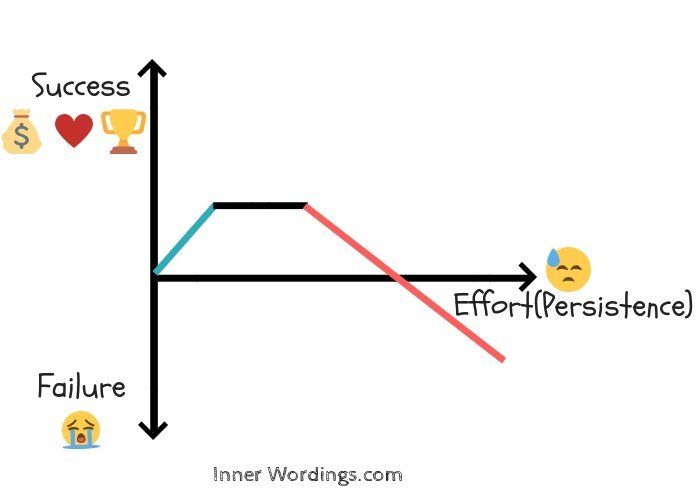

What the sunk cost effect means, is that for a lot of things, more effort does not equal more success. Instead, the relationship can actually look more like this:

Why the sunk cost effect happens

What if I told you that I tore up a $100 note yesterday? And then I burned the pieces, and flushed the ashes down the toilet. I was feeling bored.

Feeling pissed off at the thought of all that waste?

Abandoning something that we’ve invested a lot in feels like we’ve wasted everything. This is not a pleasant feeling. Why exactly do we hate the idea of wasted investments and sunk costs so much, even if they are other people’s? Let’s look deeper into our minds to see why :

1. We hate losses more than we love gains

Let’s flip a coin:

Heads: I pay you $50

Tails: You pay me $50

Would you agree? Most people wouldn’t. (If you would, congratulations on not being like the majority)

Our brains are wired to be fundamentally loss-averse: in most risky situations, the losses that we might incur matter more to us than the (equivalent) gains we might make.

This drive to avoid losses makes us do strange things. Rather than admit a sure loss now, we’re willing to take a gamble on things getting better if we stay. We don’t recognize the basic paradox behind this way of thinking: We waste what we have now, to prove that we were not wasteful in the past.

2. We’re good at justifying things

The greater the effort we put into something, the more attached we get and the more we convince ourselves that it will work out. We use our self-justification skills to convince ourselves to stay and create a vicious cycle of escalating commitment:

How do we justify things? One of these 3 ways:

- Hype up the good (“My boss is usually an a*****e , but he approved my new $0.01 raise, so … he really does appreciate me after all!)

- Downplay the bad (“Yes, we’re not meeting our expected sales targets, but we’re a long way off from being bankrupt!”)

- Tell ourselves that the things that went wrong were out of our control. (“The only reason I’m currently not losing weight is that it’s the holiday season. It makes everyone put on a few pounds, right?”)

Our confirmation bias enables us to tell ourselves whatever we want to hear and ignore contradicting evidence.

3. We’re bad with change

Maintaining the status-quo is usually the cognitively easier thing to do. Deciding to change and stop doing whatever we were doing will involve a lot of mental discomfort and stress.

We’ll have to acknowledge (to ourselves at the very least) that we may have been wrong all along. We need to figure out what new thing we should do instead. All while dealing with the fear of the unknown.

In this case, persisting on a course of action, even a failing one, is just easier on our brains.

The solution to the sunk cost effect

So, if the major reason for the sunk cost fallacy is that we frame sunk costs as losses that we need to justify, and that change is hard even if the current situation is not really working out, what is the solution?

Stop focusing on sunk costs as losses and obligations in the first place.

Focus on the gains and opportunities you’ve been granted instead.

As an example, my friend and I once had to take a horrifically boring accounting class. We didn’t feel like we were actually learning anything by going to class, and the material was easy enough to learn by ourselves. My friend still went to class, only because she had “already paid for it”.

Going to class had become her dreaded obligation to fulfill.

I, on the other hand, had a much less admirable attendance record in that class than she did. The fact that I’d already paid for the class didn’t bother me. Instead, I thought about all the things I could do with this free time.

Not going to class had become my opportunity to do virtually anything else that wouldn’t bore me out of my mind.

We both had similar results come exam time. The difference was that I had enjoyed myself the whole semester, while she hadn’t.

When to quit.. and not

Whenever you find yourself wanting to quit but conflicted over all that you’ve already invested, ask yourself two questions:

1. What are all the opportunities/gains that I could have if I quit?

2. If I were given the opportunity to start this experience from scratch, knowing it would turn out exactly the same way, would I still do it all over again?

Answer these two questions as honestly as you can. Then, and only then, make your decision.

If you quit, you’ve probably saved yourself from more stress later on.

If you persist, you can do so confidently knowing that you’re truly making a rational decision that will take you closer to success.