Quick question: Is it morally acceptable to call your parents by their first name?

You might give me a nuanced answer and say, “Well…… I wouldn’t do it myself because my parents would be upset, but if other people do it and their parents are fine with it, then it’s alright. Nobody is being hurt.”

If you grew up in a conservative, traditional or eastern household, you might say “Hell no! People who do that are degenerates.”

Or… you might have grown up in an ultra-progressive (western) home where you did call your parents by their first names, in which case you’re wondering what all this fuss is about.

The Paradox of Morality

Most of us realize that not everyone shares our values and morals. This is especially the case in the modern world, where we’re constantly exposed to people from different backgrounds and recognize that we all see the world in very different ways.

But most of us also feel that everyone should share our values and morals.

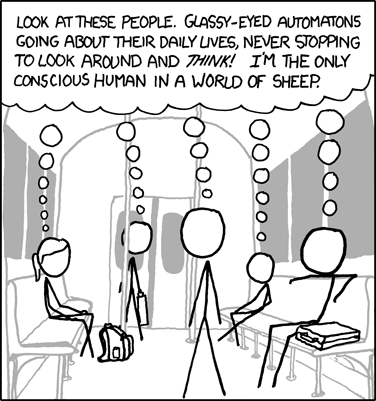

We tend to feel that our thoughts, opinions and ways of looking at the world are the “right” and “correct” options. If other people feel differently, it’s because they’re evil, stupid, misinformed, or taught the wrong things as children.

Moral absolutism – A problem

This belief in the superiority of our convictions is a driver of moral absolutism, which is the belief that all actions are either intrinsically right or wrong. The problem with being a moral absolutist, however, is that we will never fully agree on what is right or wrong. Bitter culture wars rage on between people in every country, and between countries themselves. There is no concrete set of ideas of right vs wrong that remains consistent across different cultures:

- Some countries criminalize all homosexual activity; others celebrate same-sex marriage.

- Some countries outlaw abortion completely; others give pregnant women personal choice in the matter.

- Some cultures worship critical thinking and science; others promote conforming to societal expectations and religious dictates.

Now, you might have definitive views on each of the topics above. You’re entitled to them. I just want to point out one thing:

Cultural and group morality evolves over time.

Just as we look at the past and condemn those who practiced slavery, honour killings or child marriage (which are all still being practiced in some form in many countries today), our descendants will view us as immoral for many of our current actions. As examples, they may see cruelty in our treatment of animals, callousness in our handling of the environment, and greed in our materialism and consumerism.

So then… why should anyone of us view the opinions of our particular cultural group at this moment in time as the only morally correct option for all cultures for all of time? Just think of how much your own opinions have changed over the years. They are likely to keep evolving. Moral absolutism is definitely one way to approach the world, but it may not be one that serves us well. We run dual risks of engendering continuous conflict with others as well as not changing with the times.

Moral Relativism- Also a Problem

The opposite of moral absolutism is moral relativism. Moral relativists say that since every culture and time period has its own ideas of right and wrong, we can judge someone’s actions only according to the standards of their particular culture or time period. Extreme relativists would have us judge nothing, saying that all cultural practices and values are equally as valid as each other, and so we must be tolerant of everything.

You can see the problem with moral relativism when taken to an extreme. Most people would struggle to say that there was nothing morally wrong with past slavery or genocide (even if both were normal social practices throughout history). Many cultures today still practice child marriage and female genital mutilation – should we continue to tolerate these practices as well?

Moral relativism brings its own share of headaches with its “everything goes” attitude in claiming that there is nothing inherently right or wrong. Strangely, it is also absolutist in dictating “tolerance” as a standard that we must follow. How can society function if we are to have no standpoint to judge the appropriateness or inappropriateness of any action?

“It is possible that the distinction between moral relativism and moral absolutism has sometimes been blurred because an excessively consistent practice of either leads to the same practical result—ruthlessness in political life.”

Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform

How Understanding Moral Differences Can be Valuable

The debate between moral absolutism and relativism is complex and has raged on for centuries. Rather than trying to establish which side is better, I will devote the rest of this post to describing how understanding such moral differences can improve your life. You can leverage an understanding of moral differences to:

- Empathize with other people

- Discuss, debate and negotiate issues more effectively

- Change other people’s minds

This process of understanding starts with internalizing the following idea:

We all have the right to our own moral and value system.

Now, this isn’t because all views and morals are equally as valid or correct as each other, like the (extreme) relativists would say. This approach is mostly about pragmatism: we can continue to believe that our views may be “correct”, and still show other people the basic respect of listening to them and genuinely trying to understand their point of view.

This show of respect is crucial in making the other side more likely to hear us out in return and in time change their mind. If we do the opposite and completely deny someone the validity of their views, like we usually tend to do in a fight, neither party gains anything other than self-righteous indignation.

How to Approach and Conquer Moral Differences

1. Understand the 6 moral foundations

Moral Foundation Theory was developed by social psychologist Jonathan Haidt. According to the theory, there are 6 broad foundations that individuals and groups use to judge the morality of an action:

- Care vs Harm: The Care foundation underlies virtues of being kind, gentle, and nurturing, especially to vulnerable people or groups. We are sensitive to signs of suffering and need, and are moved to act against cruelty.

- Loyalty vs Betrayal: This foundation is related to the virtues of belonging, patriotism and self-sacrifice for the group – the “all for one and one for all” mentality. We reward “team players” and can hurt, ostracize or even kill people that betray us.

- Fairness vs Cheating: People like to see a sense of proportionality and justice in outcomes i.e. that people get what they deserve and don’t get what they don’t deserve. This foundation is also related to the idea of reciprocal altruism – of helping others in the expectation they may help us one day as well.

- Authority vs Subversion: This foundation underlies virtues of leadership and followership, including obeying legitimate authority and respecting traditions. This foundation was shaped by our long history of hierarchical social interactions, which helped to create and maintain order and fend off chaos.

- Liberty vs Oppression: People are primed to recognize and resist attempted domination, and to resist bullies and tyrants. (Its intuitions often conflict with those of the authority foundation.) Our hatred of bullies and dominators motivates people to come together to oppose or take down the oppressor.

- Sanctity vs Degradation: This foundation is shaped by disgust and fear at being contaminated. According to Haidt, it also behind “religious notions of striving to live in an elevated, less carnal, more noble way. It underlies the widespread idea that the body is a temple which can be desecrated by immoral activities and contaminants.”

2. Understand that everyone varies on the relative importance of these foundations

Let’s go back to that first example where I asked you if it is morally acceptable to call your parents by their first name.

- If you said no, it is likely because you highly value authority.

- If you said yes, it is likely because you highly value liberty.

- If you gave a nuanced answer, “I wouldn’t do it myself, but others can if their parents are ok with it”, you do value authority, but not as much as you do liberty and care.

Every person and every group varies in the relative importance they assign to each of the 6 domains.

- Research shows that those who are politically liberal or progressive tend to highly value care, fairness and liberty. They assign relatively low value to the domains of authority, loyalty and sanctity. Political conservatives, on the other hand, value all 6 foundations roughly equally. Libertarians mostly care about liberty (shocker, I know) and tend to ignore the other foundations.

- Western nations are more individualistic and typically value authority and sanctity less than eastern ones.

- Women generally value care, fairness and sanctity higher than men do.

Here we must come to another understanding:

You cannot make someone else value a moral domain that you value, and not value what you don’t value.

People’s moral beliefs and attitudes are based on their experiences in life – what they were taught to believe as children, and what they have found to be true in their personal experiences. If somebody doesn’t value sanctity as much as you’d like, no amount of preaching to them is going to change their mind. If you try to impose your moral foundations on others, you will likely not be happy with the results.

3. Understand that disagreements are primarily caused by differences in morals, not lack of rationality

In this increasingly polarized world, there is no shortage of fights and conflicts over personal, political and religious matters, even among family members. Too often we take a “rational” approach to the argument, where we try to convince the other side why we’re right by using facts and logical appeals.

This never works.

Here’s the 101 on facts. We don’t use facts (or logic) to make moral judgements and decisions. We make our judgements based on our intuitions on what is right and wrong. These intuitions come from our existing values and morals. We then use the facts to justify our position.

In other words, our values come first, reasoning second.

This is why the phenomenon of confirmation bias is so hard to defeat. Each one of us only pays attention to the facts that validate what we already feel is true. Anytime we’re faced with an inconvenient fact, we find ways to discount or discredit it. And this is why an argument based on factual appeals will fail to convince another person to change their mind.

Consider the following topics, where the central conflict is caused by people valuing different moral domains differently:

- Abortion: Socially conservative and/or religious people usually see abortion as violating the sanctity of life, while progressives see abortion restrictions as a threat to women’s liberty.

- Welfare benefits and aid for poor/unemployed people: Economically conservative people see handing out aid to poor people as a betrayal of fairness – they believe that only those who work hard should be rewarded for their efforts. On the other hand, people who support welfare focus on the care principle – the notion that we have a moral obligation to help disadvantaged people and groups.

- Social distancing and mask-wearing: It seems like people who refuse to do either in the wake of COVID-19 do so because they feel their liberty is under threat from tyrannical governments and fear-mongering media channels. Others may be following COVID guidelines out of deference to authority (via government regulations and the recommendations of medical experts), sanctity (avoiding contamination) and/or care (trying to not spread the disease to others).

Now, I’m not saying that people can’t be self-serving in which morals they choose to abide by. People in positions of authority can abuse others lower in the hierarchy and say they have a right to do so. People can also claim they have a right to do almost anything in the name of liberty. The idea is not to focus on whether we think their actions are right or wrong, but to focus on how they’re likely justifying their actions to themselves.

4. Establish Rapport by Being Curious

Once we understand that most disagreements are caused due a difference in moral foundations brought about by different life experiences, and not necessarily because the other person is evil or stupid, we can get closer to understanding the other person. When we approach our conversations with others out of a sense of curiosity about their beliefs and values, rather than a sense of judgement and “You’re wrong; I’m right, listen to me”, the conversation is much more likely to serve both parties.

So, approach your discussions by being interested in the other person, neutral in your judgements and willing to understand a different point of view. When in a disagreement, ask the other person about what experiences have made them feel that way. Listen to understand, not to reply or debate. Connect their explanations and stories with the moral foundations underlying them. The objective is to establish a rapport and sense of connection with the other person.

5. Cultivate empathy by connecting with their morals

In his book Beyond Winning: Negotiating to Create Value in Deals and Disputes, Harvard Law Professor Robert Mnookin defines empathy as the process of demonstrating an accurate, non-judgmental understanding of the other side’s needs, issues, and perspective. It is not about agreeing with them or feeling sorry for them.

Imagine you’re having a disagreement with your family where they’re pushing you to do something you don’t particularly want to do – say, get married.

Their appeals to you are likely to be framed in terms of authority and tradition i.e. some version of “Everyone your age is getting married. Why won’t you just listen to us?”

You are likely to respond in terms of an argument framed in liberty – “It’s my life! I get to decide if and when I get married.”

This is not likely to persuade them.

Instead, take a step back and try to connect with the moral foundation driving them. It might be helpful to imagine or remember a situation where you felt someone did not value your authority, or your traditions weren’t being respected.

Then, you can restate their position to them, in a way that shows them you were actively listening to them and understand what they have to say. You can even add in things they might have left unsaid. E.g. “So it sounds like you feel like I’m not doing what you think I should be doing, and that you’re feeling disrespected.”

6. Frame your argument to appeal to their morals

Now that you’ve taken the time to understand the other person as much as you can, it’s time to get them to hear you out. You will be best served if you frame your argument to connect with their moral foundations rather than yours.

E.g. For parents who are busy pushing you in the name of authority and tradition, a response that might work could be, “I respect what you’re telling me, and I respect our traditions. It is because of this respect that I want to take enough time to ……. (find the right person/do things well/make sure we’re a good match etc.)”

Moral re-framing also works for political issues. For example:

- American liberals become more supportive of military spending with fairness-focused arguments that emphasize the military’s role in overcoming income equality and racial discrimination, rather than typical conservative appeals to loyalty and authority (i.e American patriotism and world dominance)

- Conservatives take a more pro-environment stance when presented with loyalty and sanctity appeals. (E.g. “Being pro-environment is the American way of life”; emphasizing how dirty and disgusting environmental pollution is.) Liberals usually focus on care (emphasizing the devastation and dangers of climate change) which is not as convincing to conservatives.

Remember: It is difficult for people to change their deep-seated morals and beliefs. Change is indeed possible, but it takes time and must be done on the person’s own terms. In any conversation, maintain respectful and empathetic dialogue, and aim only for small and incremental wins.

Summary

- Moral absolutism is the belief that all actions are inherently good or bad. The problem with moral absolutism is that we may never reach a consensus on what is good and bad and will be engaged in continual conflict with each other.

- Moral relativism is the belief that we can judge the goodness or badness of any action only according to the standards of culture and time period it was committed in. The problem with moral relativism is that leads to an “anything goes” attitude where we can excuse any action no matter how “horrible” it is to others.

- Whether you’re more of an absolutist or relativist, understanding how morality differs among people can make you a more empathetic person and a better debater/negotiator.

- When approaching and negotiating moral differences:

- Understand Moral Foundations Theory: There are 6 moral foundations that people use to judge the appropriateness of an action:

- Care vs Harm

- Loyalty vs Betrayal

- Fairness vs Cheating

- Authority vs Subversion

- Liberty vs Oppression

- Sanctity vs Degradation

- Understand that everyone varies on the relative importance of each of these domains (based on life experiences, cultural background, gender etc.)

- Understand that disagreements are caused by differences in moral foundations, rather than a lack of rationality

- Cultivate empathy by being curious about the other person’s moral foundations

- Frame your argument to appeal to the other person’s morals, not yours

- Understand Moral Foundations Theory: There are 6 moral foundations that people use to judge the appropriateness of an action: